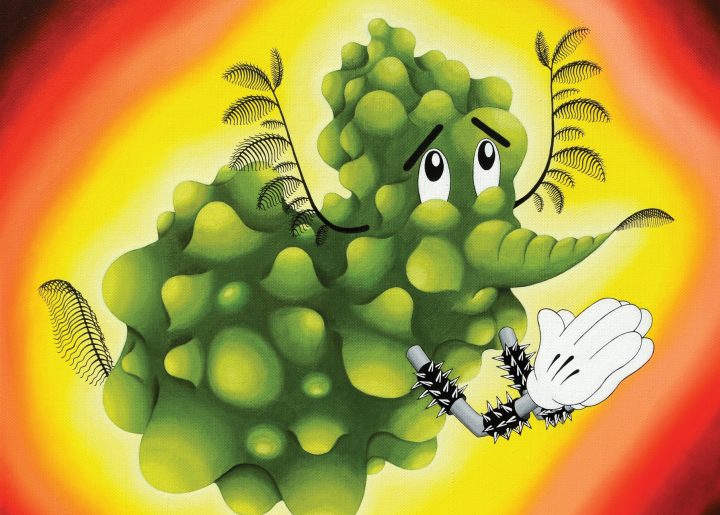

”When as a teenager I realized the world was a mire, people were whores, and true love was only possible in dreams, I found my consolation in heavy metal music. Gradually, I began discovering it – I borrowed music magazines from a fellow student, I copied cassettes and designed their covers. Ominous face expressions, bared teeth or decaying bodies accompanied me, becoming the only means to deal with the lack of perspectives and to tame lone¬liness. If metal did not save my life, it certainly helped me to men¬tally withstand the system of the poor, provincial reality during the transformation period and at the beginning of the 21st century. Art classes in my elementary school were run by a music teacher who was only familiar with Chopin and Moniuszko, the books on the curriculum were so boring you were not able to read them even if you were threatened to be beaten up, and the majority of teachers were trying to prove you were not worth a damn, if you did not solve a math or chemistry task accompanied by a ten-kilome¬ter-long description. In high school, I felt like a cockroach among the bohemians discussing jazz and wine brands. Heavy metal, with its passion for turpism, brutal Cannibal Corpse album covers and Yattering murderous lyrics, bacame my shelter, providing a feeling of safety and acceptance from other fans, outcasts and weirdos like me. Metal tamed the bestiality of the world, nothing else would surprise me. Metal, black metal in particular, is no longer the wave raised by one of the largest cultural revolutions of the late 20th century, accompanied by burning churches and murders. It be¬came a tamed middle-class entertainment, as Łukasz Orbitowski once put it. Since the trends referring to the roots of the genre continue to develop dynamically, variations carrying the original spirit of rebellion are likely to appear every now and then. I came up with the idea that my paintings would freely visualize individual sub-genres of metal music, with all their characteristics: logos, mascots, musicians, typical fans, technical crew, prototype guitar amplifiers made to order for village-based musicians or black/death metal machines for grinding the human mob. The image is depicted in a crooked mirror, as it is difficult to take metal without a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, it is an expression of my fascination and a sentimental self-examination. Although the images are served with an acid sauce, they contain a hint of narrative – something I used to avoid in the past. Absurd and irony – which offer a way to alleviate the seriousness of exist¬ence and pseudo-intellectual, humorless art gibberish – mix with a satanic sublimity, while rural folklore blends with industrialism. As a former altar boy I have had to come to terms with the dark side of the power. Metal inspired paintings are sharp, they refer to the symbols commonly associated with the genre: pentagrams, inverted crosses, alongside objects from the provincial world: car tyre sculptures and garden ornaments. The sculptures depict our desire to surround ourselves with hand-processed things. Joyful interferences in the nearest environment, they symbolize an at¬tempt to find beauty in objects of everyday use or to repurpose the broken items. At the same time, they reflect aesthetic taste distorted by the prism of poverty. I photograph selected paintings in a setting inspired by the image characteristic of metal musi¬cians, at the same time calling attention to their rural origin. There is something hallucinogenic about folklore, and that is true of the whole Silesia, not only Grupa Janowska or Oneiron. The music scene has its psychedelic autonomy. From hip-hop performers including Kaliber 44 to metal itself, with outstanding songwriters including Roman Kostrzewski of the legendary Kat or a number of black metal bands with Furia’s frontman Nihil at the forefront.”

Marek Rachwalik